Trevor Huddleston on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Urban Trevor Huddleston (15 June 191320 April 1998) was an English

Huddleston's community asked him to return to England in 1955 (and he left South Africa in early 1956), some say due to the controversy he was attracting in speaking out against apartheid. However, the Superior at the time, Raymond Raynes, wrote that the decision to recall Trevor was made by Raynes himself. In 1956 he published his seminal work, ''Naught for your Comfort'', and began work as the master of novices at CR's

Huddleston's community asked him to return to England in 1955 (and he left South Africa in early 1956), some say due to the controversy he was attracting in speaking out against apartheid. However, the Superior at the time, Raymond Raynes, wrote that the decision to recall Trevor was made by Raynes himself. In 1956 he published his seminal work, ''Naught for your Comfort'', and began work as the master of novices at CR's

Huddleston died at

Huddleston died at

Audio samplesObituary by Aelred Stubbs

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20061211143800/http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/history/solidarity/huddlepress.html ''Items from the Press on the Death of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston'': ANC websitebr>Trevor Huddleston CR Memorial Centre, Sophiatown, Johannesburg, South Africa''Naught for Your Comfort''

online text at archive.org {{DEFAULTSORT:Huddleston, Trevor 1913 births 1998 deaths 20th-century Anglican archbishops Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Anglican archbishops of the Indian Ocean Anglican bishops of Masasi Anglican bishops of Mauritius Bishops of Stepney British expatriates in South Africa 20th-century Church of England bishops English religious writers Housing in South Africa Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Members of Anglican religious orders People educated at Lancing College People from Bedford 20th-century Anglican bishops in Tanzania

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. He was the Bishop of Stepney

The Bishop of Stepney is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of London, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after Stepney, an inner-city district in the London Borough of ...

in London before becoming the second Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

of the Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean

The Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean is a province of the Anglican Communion. It covers the islands of Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles. The current Archbishop and Primate is James Wong, Bishop of Seychelles.

Anglican realign ...

. He was best known for his anti-apartheid activism and his book ''Naught for Your Comfort''.

Early life

Huddleston was the son of Ernest Huddleston and was born inBedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

, Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council wa ...

, and educated at Lancing College

Lancing College is a public school (English independent day and boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in southern England, UK. The school is located in West Sussex, east of Worthing near the village of Lancing, on the south coast of England. ...

(1927–1931), Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, and at Wells Theological College

Wells Theological College began operation in 1840 within the Cathedral Close of Wells Cathedral. It was one of several new colleges created in the nineteenth century to cater not just for non-graduates, but for graduates from the old universiti ...

. He joined an Anglican religious order, the Community of the Resurrection

The Community of the Resurrection (CR) is an Anglican religious community for men in England. It is based in Mirfield, West Yorkshire, and has 13 members as of February 2021. The community reflects Anglicanism in its broad nature and is stron ...

(CR), in 1939, taking vows in 1941, having already served for three years as a curate at St Mark's Swindon

Swindon () is a town and unitary authority with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Wiltshire, England. As of the 2021 Census, the population of Swindon was 201,669, making it the largest town in the county. The Swindon un ...

. He had been made a deacon at Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

1936 (27 September) and ordained a priest the following Michaelmas (26 September 1937) — both times by Clifford Woodward, Bishop of Bristol

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, at Bristol Cathedral

Bristol Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is the Church of England cathedral in the city of Bristol, England. Founded in 1140 and consecrated in 1148, it was originally St Augustine's Abbey but after the Dissolu ...

.

South Africa

In September 1940 Huddleston sailed toCape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, and in 1943 he went to the Community of the Resurrection mission station at Rosettenville (Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

, South Africa). He was sent there to build on the work of Raymond Raynes, whose monumental efforts there, building three churches, seven schools and three nursery schools catering for over 6,000 children, had proved to be so demanding that the community summoned him back to Mirfield in order to recuperate. Raynes was deeply concerned about who should be appointed to succeed him. He met Huddleston who had been appointed to nurse him while he was in the infirmary. As a result of that meeting, much to Huddleston's surprise as he had only been a member of the community for four years, Raynes was convinced that he had found his successor.

Over the course of the next 13 years in Sophiatown

Sophiatown , also known as Sof'town or Kofifi, is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. Sophiatown was a black cultural hub that was destroyed under apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "apart ...

, Huddleston developed into a much-loved priest and respected anti-apartheid activist, earning him the nickname ''Makhalipile'' ("dauntless one"). He fought against the apartheid laws, which were increasingly systematised by the Nationalist government which was voted in by the white electorate in 1948, and in 1955 the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

(ANC) bestowed the rare Isitwalandwe award of honour on him at the famous Freedom Congress in Kliptown

Kliptown is a suburb of the formerly black township of Soweto in Gauteng, South Africa, located about 17 km south-west of Johannesburg. Kliptown is the oldest residential district of Soweto, and was first laid out in 1891 on land which form ...

. He was particularly concerned about the Nationalist Government's decision to bulldoze Sophiatown and forcibly remove all its inhabitants sixteen miles further away from Johannesburg. Despite Huddleston's efforts, these removals began on 9 February 1955 when Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

described Huddleston as one of the leaders of the opposition to the removal. Among other work, he established the African Children's Feeding Scheme (which still exists today) and raised money for the Orlando Swimming Pools – the only place black children could swim in Johannesburg until post-1994.

There are many South Africans whose lives were changed by Huddleston; one of the most famous is Hugh Masekela

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela (4 April 1939 – 23 January 2018) was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who was described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for ...

, for whom Huddleston provided his first trumpet as a 14-year-old pupil at St. Martin's School (Rosettenville) in South Africa. Soon after the ‘Huddleston Jazz Band’ was formed, sparking a global career for Masekela and his fellow South African, Jonas Gwangwa

Jonas Mosa Gwangwa (19 October 1937 – 23 January 2021) was a South African jazz musician, songwriter and producer. He was an important figure in South African jazz for over 40 years.

Career

Gwangwa was born in Orlando East, Soweto. He firs ...

. Other notable persons who credit Huddleston with influencing their lives include Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

, Sally Motlana, (activist and vice-chair of the South African Council of Churches

The South African Council of Churches (SACC) is an interdenominational forum in South Africa. It was a prominent anti-apartheid organisation during the years of apartheid in South Africa. Its leaders have included Desmond Tutu, Beyers Naudé an ...

during the 1970s); Archbishop Khotso Makhulu and Robben Island

Robben Island ( af, Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrik ...

er and later President of the Land Claims Court, Fikile Bam. Huddleston was close to O R Tambo, ANC President during the years of exile, from 1962 to 1990. They hosted many conferences, protests and actions together, in the face of fierce opposition from both Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, and the South African government and their allies.

Return to England, Tanzania and Mauritius

Huddleston's community asked him to return to England in 1955 (and he left South Africa in early 1956), some say due to the controversy he was attracting in speaking out against apartheid. However, the Superior at the time, Raymond Raynes, wrote that the decision to recall Trevor was made by Raynes himself. In 1956 he published his seminal work, ''Naught for your Comfort'', and began work as the master of novices at CR's

Huddleston's community asked him to return to England in 1955 (and he left South Africa in early 1956), some say due to the controversy he was attracting in speaking out against apartheid. However, the Superior at the time, Raymond Raynes, wrote that the decision to recall Trevor was made by Raynes himself. In 1956 he published his seminal work, ''Naught for your Comfort'', and began work as the master of novices at CR's Mirfield

Mirfield () is a town and civil parish in Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the A644 road between Brighouse and Dewsbury. At the 2011 census it had a population of 19,563. Mirfield f ...

mother house in West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

for two years before becoming the prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

of the order's priory in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

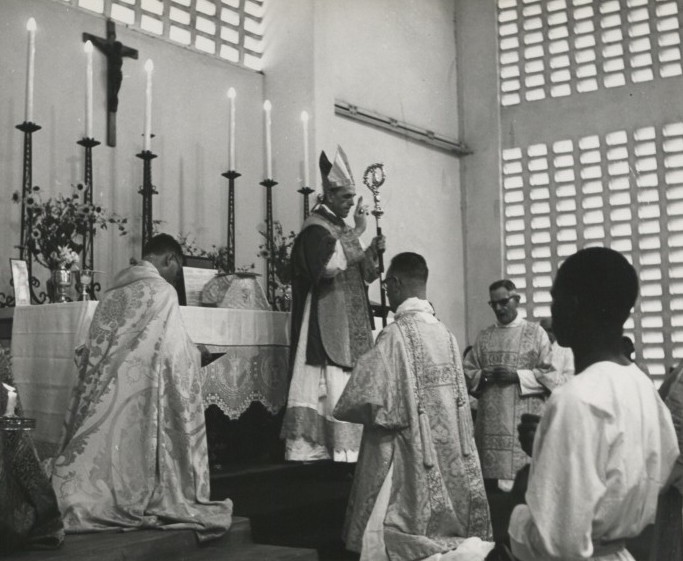

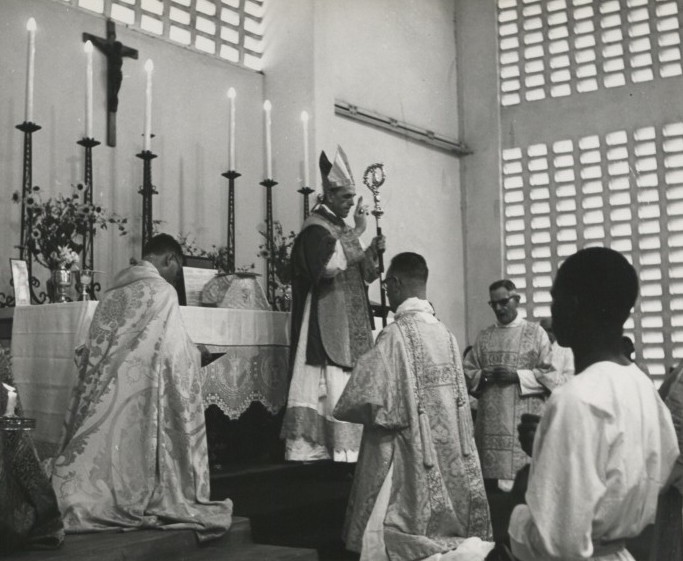

where he remained until his appointment as a bishop. He was consecrated a bishop on St Andrew's Day

Saint Andrew's Day, also called the Feast of Saint Andrew or Andermas, is the feast day of Andrew the Apostle. It is celebrated on 30 November (according to Gregorian calendar) and on 13 December (according to Julian calendar). Saint Andrew is ...

1960 (30 November) by Leonard Beecher

Leonard James Beecher (21 May 190616 December 1987) was an English-born Anglican archbishop. He was the first archbishop of the Province of East Africa, comprising Kenya and Tanzania, from 1960 to 1970.

Education and training

He was educated at ...

, Archbishop of East Africa, at St Nicholas', Ilala, Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (; from ar, دَار السَّلَام, Dâr es-Selâm, lit=Abode of Peace) or commonly known as Dar, is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over s ...

, to serve as Bishop of Masasi (Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

), where he worked for eight years, primarily in re-organising the mission schools to be run by the newly independent government of Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, aft ...

, with whom he became a firm friend. He became Bishop of Stepney

The Bishop of Stepney is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of London, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after Stepney, an inner-city district in the London Borough of ...

, a suffragan bishop

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Anglican Communion, a suffragan bishop is a bishop who is subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop (bishop ordinary) and so is not normally jurisdiction ...

in the Diocese of London

The Diocese of London forms part of the Church of England's Province of Canterbury in England.

It lies directly north of the Thames. For centuries the diocese covered a vast tract and bordered the dioceses of Norwich and Lincoln to the north ...

.

In 1974, Huddleston was questioned by the police in connection with complaints of alleged sexual abuse made by the parents of four boys who had been playing in Huddleston's office. In his statement Huddleston said "I have never done anything to harm a child ... Neither do I consider it indecent to pat a child on the bottom or pinch him ... The boys are telling the truth but the implications of indecency are completely absurd." The police report recommended charging him with four counts of gross indecency, but because of his high profile, the matter was referred to the director of public prosecutions

The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) is the office or official charged with the prosecution of criminal offences in several criminal jurisdictions around the world. The title is used mainly in jurisdictions that are or have been members o ...

, Sir Norman Skelhorn. Skelhorn decided not to charge him after consulting Labour party figures. According to some sources, the existence of the investigation and report was only uncovered as part of research for the 2004 publication of Piers McGrandle's biography (see below). However, there was no reason for the report to be public, if the case for prosecution had been dismissed.

In his biography, ''Trevor Huddleston: Turbulent Priest'', Piers McGrandle quotes Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Bishop Gerald Ellison

Gerald Alexander Ellison (19 August 1910 – 18 October 1992) was an Anglican bishop and rower. He was the Bishop of Chester from 1955 to 1973 and the Bishop of London from 1973 to 1981.

Early life and education

Ellison was the son of a chaplai ...

dismissing the claims as a plot by the South African Bureau of State Security

The Bureau for State Security ( af, Buro vir Staatsveiligheid; also known as the Bureau of State Security (BOSS)) was the main South African state intelligence agency from 1969 to 1980. A high-budget and secretive institution, it reported directly ...

(B.O.S.S.) to discredit a prominent opponent of apartheid. Tutu wrote the foreword for the McGrandle book, and Archbishop Rowan Williams the afterword. McGrandle was a part-time chaplain to Huddleston, and wanted to introduce Huddleston to a new generation. At a service to mark the Centenary of Huddleston's birth in June 2013, many people testified to the impact Huddleston had made on their faith and practice as Anglicans, and others, as activists.

Tutu, who as a little boy knew Huddleston and swears to his innocence, was particularly affronted by the suggestion that Huddleston was anything other than a protector of children. On 14 February 1995 he wrote a lengthy letter saying any suggestion of Huddleston's criminality was outrageous and adding that he could easily gather together a dozen black friends of Huddleston's acquaintance who would testify to his innocence and integrity.

On 14 February 1995, Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

, the then Archbishop of Cape Town wrote: "He uddlestonwas an enormous thorn in the side of the apartheid regime and was effectively the real spokesman for the anti-apartheid movement for a considerable period. No one did more to keep apartheid on the world's agenda than he and therefore it would have been a devastating victory for the forces of evil and darkness had he been discredited", adding "How ghastly to want to besmirch such a remarkable man, so holy and so good. How utterly despicable and awful."

Bishop Gerald Ellison, the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

when Huddleston was Bishop of Stepney, also said that political enemies of Huddleston were involved.

Ellison said: "I want to make it absolutely clear that I have seen no evidence that Bishop Trevor was ever guilty of a criminal act. He undoubtedly had many enemies in South Africa and England who wanted to denigrate him, indeed, to destroy him." Ellison was also clear that neither he, nor his legal advisers, believed anyone had the right to impede justice if there was any real evidence of guilt. However Sam Silkin, the Attorney General at the time who had taken the decision not to prosecute, later said on the radio:

::”I found that I was in difficulty as the man was very well known. If he had been prosecuted at all it would have ruined his career. Within the DPP

DPP may stand for:

Business

*Digital Production Partnership, of UK public service broadcasters

* Direct Participation Program, a financial security

* Discounted payback period

Photography

* Digital Photo Professional, Canon software

Law en ...

’s department everyone thought he would be acquitted, though there was clearly evidence.”

After 10 years in England, Huddleston was appointed (1978) as the Bishop of Mauritius The Bishop of Mauritius () has been the Ordinary of the Anglican Church in Mauritius in the Indian Ocean since its inception in 1854. The current bishop is Ian Ernest, who was also the Archbishop of the Indian Ocean until 2017.

Bishops

*1854 Vin ...

, a diocese of the Province of the Indian Ocean

The Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean is a province of the Anglican Communion. It covers the islands of Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles. The current Archbishop and Primate is James Wong, Bishop of Seychelles.

Anglican realign ...

. Later in the same year he was elected as the Archbishop of the Province of the Indian Ocean. In 1984, he was succeeded by Rex Donat

Luc Rex Victor Donat GOSK (known as Rex) was the fourteenth Anglican Bishop of Mauritius, succeeding in 1984 the Most Revd. Trevor Huddleston. Earlier on, in 1967, Donat became the first Mauritian Warden of Saint Andrew's School, the only Angli ...

as Bishop of Mauritius.

After retirement

After his retirement from episcopal office in 1983, Huddleston continued anti-apartheid work, having become president of theAnti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

in 1981. He continued to campaign against the imprisonment of children in South Africa, and was able to vote as an honorary South African in the first democratic elections on 27 April 1994. He briefly returned to South Africa but found it too difficult with his diabetic condition and increasing frailty, and returned to Mirfield. In October 1994 he was involved in the establishment of the Living South Africa Memorial, the UK's memorial to all those who lost lives under political violence, at St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

church, London, which raised funds for education in the newly democratic South Africa, and campaigned for ongoing investment in the region, under a call to action 'It takes more than a vote to get over apartheid'.

In 1994, he received honours from Tanzania ( Torch of Kilimanjaro) and was awarded the Indira Gandhi Award for Peace, Disarmament and Development. In the 1998 New Year Honours

The New Year Honours is a part of the British honours system, with New Year's Day, 1 January, being marked by naming new members of orders of chivalry and recipients of other official honours. A number of other Commonwealth realms also mark this ...

he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(KCMG).

In 1994, Huddleston was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.) degree from Whittier College

Whittier College (Whittier Academy (1887–1901)) is a private liberal arts college in Whittier, California. It is a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) and, as of fall 2022, had approximately 1,300 (undergraduate and graduate) students. It was ...

.

Death and legacy

Huddleston died at

Huddleston died at Mirfield

Mirfield () is a town and civil parish in Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the A644 road between Brighouse and Dewsbury. At the 2011 census it had a population of 19,563. Mirfield f ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

, England, in 1998. A window in memory of him is in Lancing College

Lancing College is a public school (English independent day and boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in southern England, UK. The school is located in West Sussex, east of Worthing near the village of Lancing, on the south coast of England. ...

chapel and was visited by Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

. They had become friends when Huddleston visited a young Tutu in hospital when he was ill with TB. They later worked together opposing apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

. The Huddleston Centre in Hackney has been delivering youth provision to disabled young people living in Hackney for over 30 years, and continues to do so. The centre bears Huddleston's name after he intervened to ensure that part of a church building was converted to provide an accessible nursery, play (and latterly youth club) space for disabled young people in Hackney, regardless of their faith. The Trevor Huddleston Memorial Centre in Sophiatown was established in 1999 following Huddleston's death and the interment of his ashes in the garden of Christ the King Church in Sophiatown where he had been active and then supervised mission activity for 13 years. The Centre delivers youth development programmes in Johannesburg as well as heritage and cultural projects promoting Huddleston's belief in developing the potential of every young person and his commitment to non-racialism

Non-racialism, aracialism or antiracialism is a South African ideology rejecting racism and racialism while affirming liberal democratic ideals.

History

Non-racialism became the official state policy of South Africa after April 1994, and it is en ...

, multi-faith issues and social justice.

In addition, he also bought the first trumpet of Hugh Masekela

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela (4 April 1939 – 23 January 2018) was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who was described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for ...

, a South African trumpeter, composer and singer, and got Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and several era ...

to give Masekela one of his own trumpets as a gift. Aged 21, Masekela left South Africa for the UK where Huddleston helped him secure a place at the Guildhall School of Music, and then he went to New York, where he began to craft his signature Afro-jazz style, under both Armstrong and Gillespie. Masekela was joined at the event by special guest and New York-born jazz pianist, Larry Willis, whom Masekela first met in those early days in Manhattan. Masekela later gave the Fr Huddleston Memorial Lecture at a special event in central London to mark the end of Huddleston's Centenary Year (June 2013-June 2014), and the 20th anniversary of democratic elections.

Hosted by the Trevor Huddleston Memorial Centre (based in Sophiatown, Johannesburg), the Gala Evening raised funds for the work of the Memorial Centre, to help young entrepreneurs get a foothold in the creative industries in South Africa. The Memorial Centre runs training and incubation for entrepreneurs, and awards the Fr Huddleston Arts Bursary to one young South African annually, giving them experience in a UK community arts setting for 3–6 months. In this way, the legacy of Huddleston in assisting young people is continued.

Writings

Books

Huddleston wrote five books, the seminal two being: * *Prayer for Africa

A well-known prayer of Huddleston's is the "Prayer for Africa". It has been recited throughout South Africa, Tanzania and other African countries.Alternative version (with emphasis on children):God bless Africa, Guard her people, Guide her leaders, And give her peace.

Another alternative version:God Bless Africa, Guard her children, Guide her leaders, And give her peace, for Jesus Christ's sake. Amen.

God bless Africa, God bless Africa, Guard her children, guide her leaders. God bless Africa, God bless Africa, God bless Africa and bring her peace.

See also

* Graham ChadwickNotes and references

* * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Audio samples

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20061211143800/http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/history/solidarity/huddlepress.html ''Items from the Press on the Death of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston'': ANC websitebr>Trevor Huddleston CR Memorial Centre, Sophiatown, Johannesburg, South Africa

online text at archive.org {{DEFAULTSORT:Huddleston, Trevor 1913 births 1998 deaths 20th-century Anglican archbishops Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Anglican archbishops of the Indian Ocean Anglican bishops of Masasi Anglican bishops of Mauritius Bishops of Stepney British expatriates in South Africa 20th-century Church of England bishops English religious writers Housing in South Africa Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Members of Anglican religious orders People educated at Lancing College People from Bedford 20th-century Anglican bishops in Tanzania